An Anthropological Introduction to Academic Weird Facebook

Table of Contents

Introduction

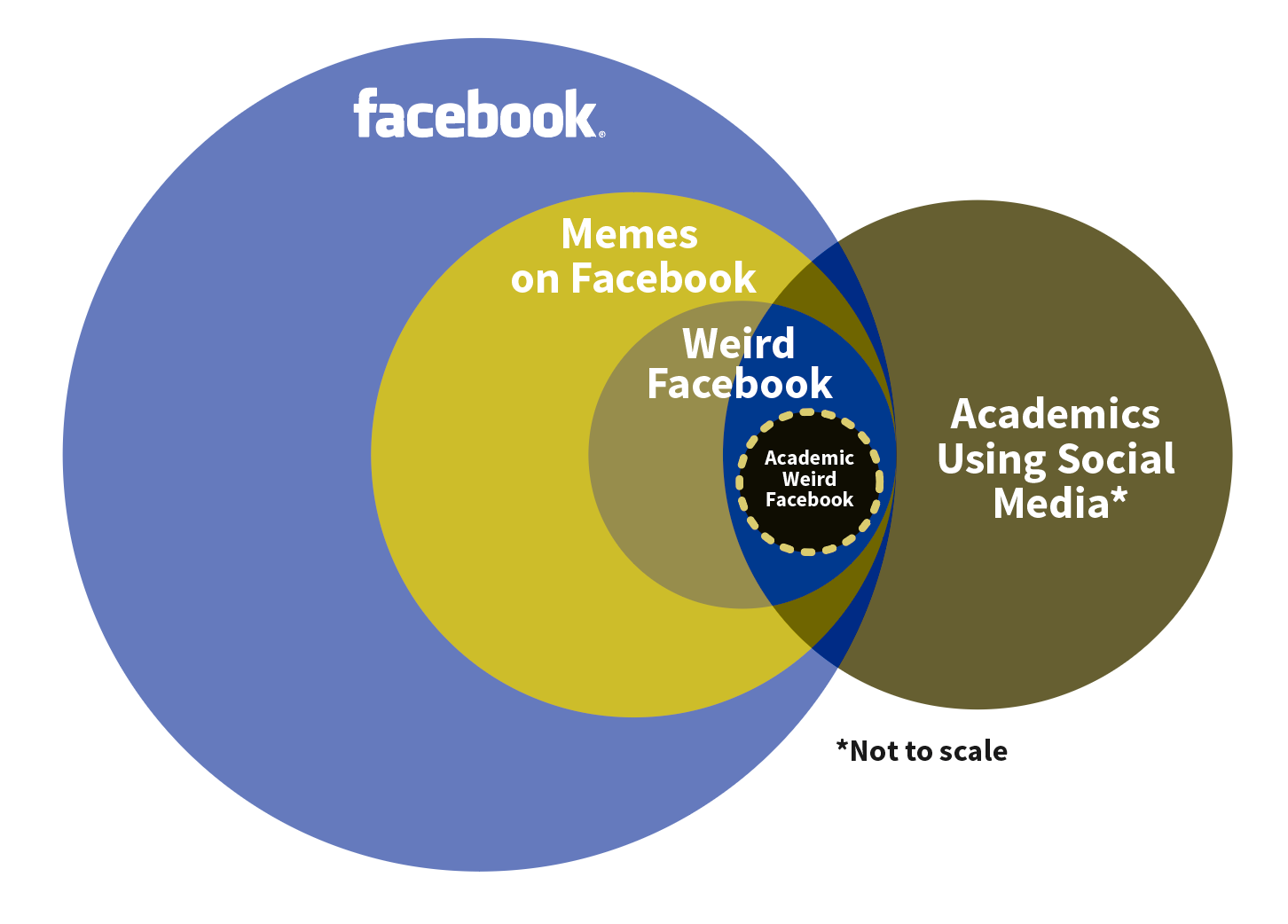

While trawling through the murky waters of social media, you might notice a peculiar image slipping through the crevices between your aunt’s cat photos and your third cousin’s passive-aggressive crypto-complaints about her ex. It bubbles up and washes ashore onto your feed like flotsam in an ocean of posts, selfies, personal updates, jokes, and statuses by more than a billion people living out the minutiae of their daily lives online; a public spectacle for people who haven’t talked to each other in months (and likely don’t plan to either). At first glance, the image looks like any old meme: it probably has a funny and distorted picture, a caption, maybe some funky fonts, emojis, or other meme memorabilia; but upon closer inspection, it’s not really like your typical meme at all—instead of talking about animals, relationships, politics, or other common topics, its punchline is about some obscure 19th century philosopher, the average word length is distinctly in the double digits, and the people in the comments section keep asking someone to explain the joke. The source of this image is a weird diaspora of the underground meme scene which has found a home for itself in the unlikeliest of places: Facebook.

I would like to paint an ethnographic picture of this community. This is by no means an unbiased account—my beliefs, attitudes, and understandings of it are informed by my personal experiences as one of its members. I’ve been a part of this community since close to the very beginning, watching it gradually simmer and then suddenly burst out in a huge flourish of frenzied activity in 2015. Besides simply being a casual participant and observer, I’ve also been one of the organizers, stewards and shepherds of my own little niche within this community, and so I have been privy to the various scales and spaces that comprise it from multiple perspectives.

The academic niche of Weird Facebook doesn’t currently have any standard naming conventions in regards to itself. There are sub-communities that do have names, such as “theorybook”, (analogous to the “Lefttube/Breadtube” spheres of Youtube creators) but these only comprise a small section of the broader community that I’m describing, so I generally refer to it simply as “Academic Weird Facebook”. From here on I will abbreviate these two communities as WFB and AWFB, respectively.

In my account of this community, I will first focus on the general practices and habits of the larger community of WFB before moving into the peculiarities of AWFB, as it is necessary to understand the former in order to understand the latter. For the purposes of this introduction, I will stick to outlining shared structures and characteristics rather than going into details about particular groups. I will also focus on describing the quality and character of the scene rather than outlining rigid criteria for inclusion or exclusion.

It’s hard to point at any one thing that can represent Weird Facebook. There’s no one page or person that defines weird facebook, and this is part of what makes weird facebook robust. Weird Facebook is an emergent property of a certain network of people.

Weird Facebook

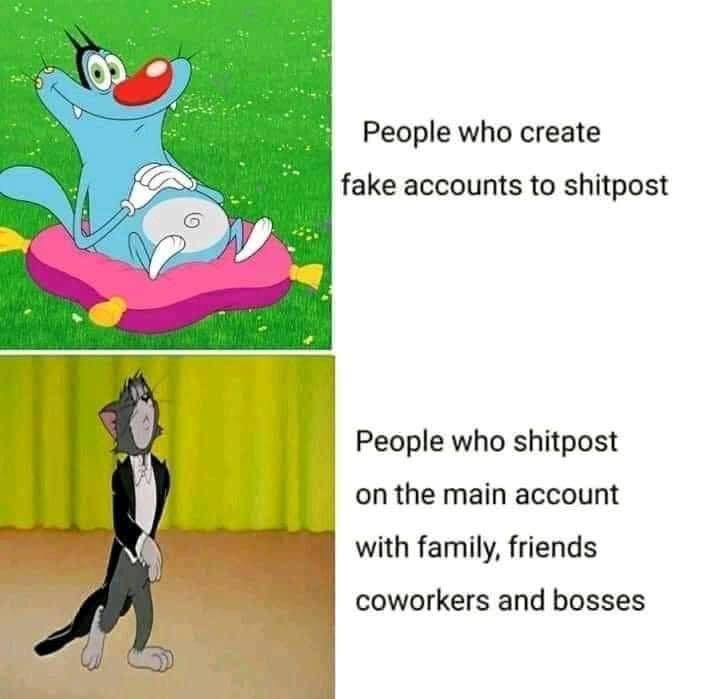

The term “Weird Facebook” comes from the misappropriation of the Facebook platform, which was originally intended for modeling real life relationships; for users to use their real-life persona and identity to connect with family, friends, classmates and co-workers. Users who do not play by these rules often suffer penalties at the hands of Facebook’s moderation and policy enforcement in the form of activity-blocking and account suspension. This tension between the policy of legitimate identity and the desires of the user base for play and entertainment illustrates what Jodi O’Brien views as the “strain between those who view online interaction as an opportunity to ‘perform’ a variety of perhaps fabricated roles versus those who see cyberspace as a new communication medium between ‘real people.’”(Kollock & Smith)1. Weird Facebookers parade behind strange names and profile pictures that don’t reflect their real life identity and use the platform to share memes and satirical, ironic and absurdist content instead of family photos. They base their social networks around memetic interactions, affiliations and communities instead of real-life relationships—befriending strangers from around the world on the basis of the perfect combo of clashing meme signifiers in their profile pictures instead of their hometowns, universities or workplaces. However, O’Brien’s dichotomy of real vs performed begins to collapse in on itself when this community is viewed in the light of the rest of Facebook.

Despite the platform owners’ claims to authenticity and their continuous efforts at ID-verification, even people who use their real names and pictures on Facebook cannot be said to be representing their authentic real-life selves. Social media has become an everyday ritual to a large part of the population and “people rarely self-identify as performers when engaging in everyday rituals, but they frequently adjust their behaviors for different audiences.” (Papacharissi)2. However, unlike the real-life everyday, where a person is apprehended from all sides in all their real-time flaws, social media gives the user the power to selectively represent themselves, choosing or hiding photos in a way that skews the persona presented online into a highly edited and staged performance. Yet the mechanics involved lead even the people posting the pictures themselves to be lulled into a sense of realism; all the images are posted from real-life events, so the whole profile looks highly realistic and believable. However, it’s not with photoshop that reality is manipulated on Facebook—it is unlikely that many people edit the actual contents of their photos—but through the self-conscious filtering, redaction and self-censorship that accompanies every single decision to-post-or-not-to-post, which gives rise to a stable and lasting representation of a human being. “In the context of social awareness systems, self-awareness and self-monitoring are heightened as individuals advance into a constant state of redaction, or editing and remixing the self.” (Papacharissi)2. In light of this factor, to qualify social media as necessarily parallel to real life is inherently disingenuous.

i never feel like the same person i was the next day but social media preserves appearances and i dont appreciate that there’s this static body of information out there that people think is me.

Weird Facebookers abandon that project altogether, instead engaging with the profile as a performance, and exploring how the human condition spills out into the procrustean bed of Facebook’s categories and functions. Users stage photos, change their names, fill in their profiles with jokes based on random meme references instead of real information, photoshop their face into memes, add weird captions and other meme characters’ faces into the images to create complex narratives. In this way, their online existence almost becomes a meme in itself, inhabiting the same space and interacting with other memes in their own dimension. Yet by doing this, they treat the platform as a world in itself—not a place to perform a re-presentation of an idealized real-life self, but as a new communication medium between people living out remote online realities, in a novel visual language—an inverted reformulation of O’Brien’s dichotomy. <!–

In the deliberately improvised performances of a digital orality, interplay between spontaneity and preparation enables individuals to blend print and oral practices of storytelling in presenting themselves.

–> Despite its rebellious nature, the WF community is nevertheless shaped by the platform it inhabits. Rather than being a faceless cohort of strangers such as on imageboards like 4chan, whose anonymity allows for the creation of a new identity with every new post, the sociability, scalability and intimacy of the Facebook platform actually connects the users in a much more meaningful way, simulating real life friendships. In much the same way, there is a blending of the personal identity of the user, which combines the constructed, meme-clique online identity with the circumstantial and contextual real life identity.

These two identities exist simultaneously, with people often participating in both regular Facebook and Weird Facebook on the same account, connecting personal, real-life social networks with online, interest-based social networks into a broad, strange, but very rich and eclectic circle of friends. There is a flattened hierarchy of intimacy between real-life friends and internet friends and everything gets posted to the same account. “Blending the public with the private, they produce what Boyd3 referred to as ‘context collapse’ for performances of sociality lacking the situational definition inherently suggested by public and private boundaries.” (Papacharissi)2. Facebook does present users with a toolkit for segregating friends into lists for post-visibility, however these are not consistently used and the two worlds often bleed into each other.

Source: Things that are not aesthetic

In fact, this clashing interaction between the meme community and the greater context of Facebook is an important influence on the style, structure, and narratives of its members: their play is often a self-aware exploration of the intended and unintended consequences and experiences of users wading through a messy social milieu where the internet is not some novelty, but a staple and mundane part of life. Their postings are the pure expression of creative freedom in a post-postmodern era where Shrek, Spongebob and fidget spinners inhabit the same space as theology, politics, astrology and cat videos within every person’s daily Facebook feed. And yet, these are not merely creative expressions of unbridled social exuberance. Behind all this frenzied activity, there looms the ever-present system of algorithms and selective pressures acting on each user, each community, each piece of content—all vying for a foothold in the unrelenting economy of attention. This pressure towards novelty, combined with a constant barrage of discordant inspiration in their social feeds, pushes users to seek novelty through remix; both as a low-hanging fruit of “easy-mode” innovation, but also as a reflection of their own experience and interests. Their increasingly avant-garde meme remixing seeks to discover the limits of human communication through irony, absurdity, and cacophony.

In a way, this frenetic recombination of memes feels like the bewildered actions of infants trying to fit square pegs into round holes in a play-set with billions of moveable parts. Unbound by artistic conventions or definitions, meme makers combine and recombine imagery like monkeys at the keyboard of a colossal meme generating machine that, given enough time, will likely permute all the possible combinations of clashing images, symbols and texts known to humankind. And yet within this chaos, there is also a glimmer of the desire to sincerely connect with others, to create meaning, to understand and critically engage with this swollen and bloated cultural corpora whose growth and velocity has massively outpaced the ability of any human to comprehend. Perhaps under these conflicting impulses and motivations, it was inevitable that some meme-makers in search of novelty eventually turned to academia as a way of enriching their repertoire, and some students, in turn, turned to memes in order to bring humor and tomfoolery into their engagement with knowledge.

Academic Weird Facebook

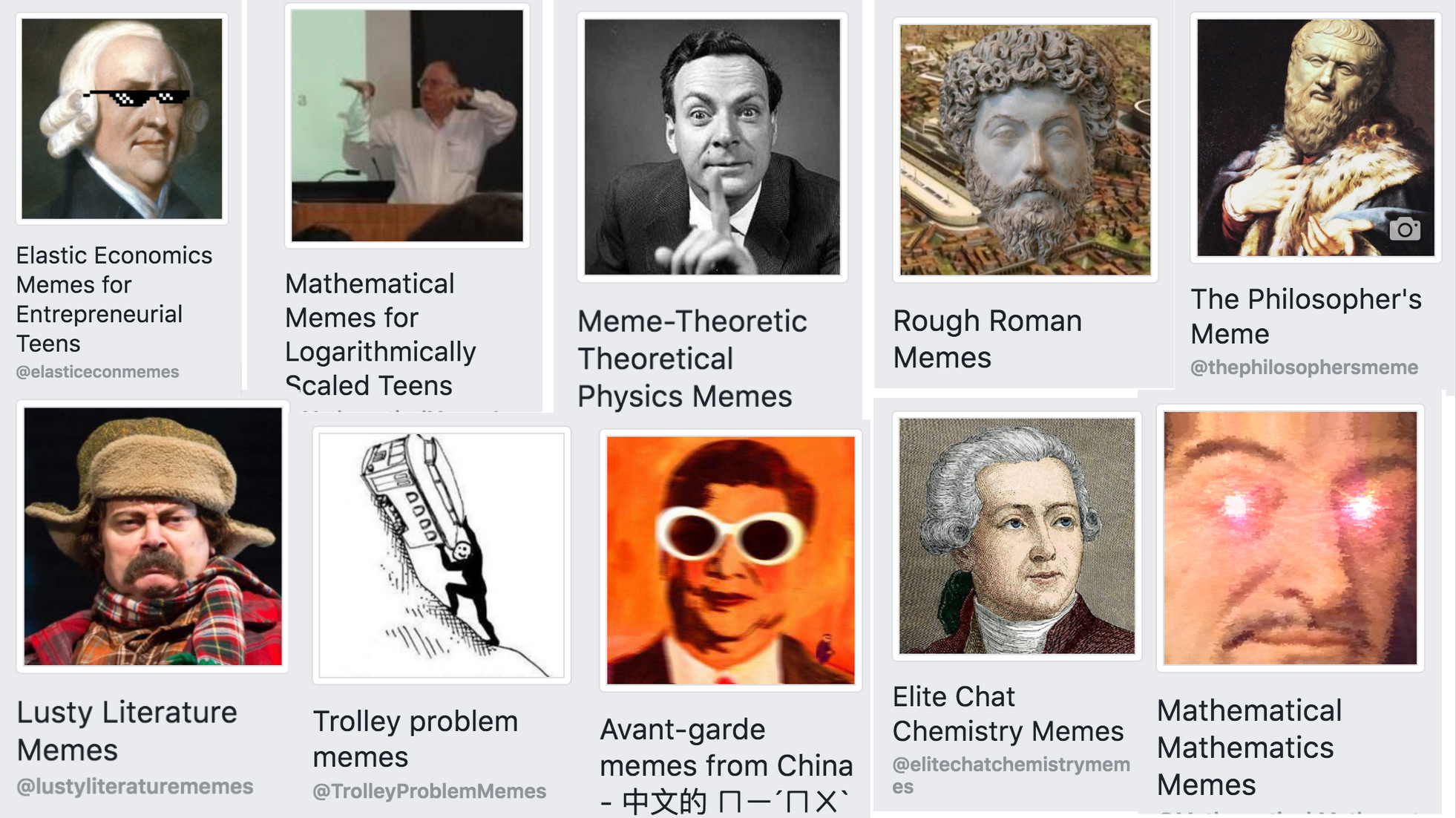

Academic jokes and memes have always existed in various corners of the internet. However, since 2015 there’s been a noticeable surge of meme content about history, philosophy, and the sciences being created and spread across social media. In tandem with the general rise of the WFB-population, hundreds of thousands of students, hobbyists, as well as serious academics are congregating around these academically oriented memepages and their porous community structures, which function as hubs for collaboration, community education, and memetic experimentation.

These intellectual meme hubs exist in parallel with the root framework of social interactions, profiles, and friend networks that comprise Facebook. The memetic content that is created in AWFB discussion groups and pages (the more public sphere on Facebook) both spills out into the more personal, profile/timeline-space (private-sphere) interactions, as well as being enriched by these private connections, in a symbiotic relationship. These new social circles facilitate innovation and the playful generation of content through everyday interactions.

Largely due to the academic orientation and proximity of this sub-community, an important component of the discourse within it is a self-conscious and reflexive conversation about its own evolving nature, stylistic conventions, community structures, rhetoric, and practices. There are a huge number of sub-niches within WFB, and even moreso within AWFB, many of them overlapping, and many others having rival or antagonistic relationships. “However, once another … group becomes involved in the discussion, such distinctions tend to collapse as each group orients itself in a monolithic manner toward the other group. Within-group variation is attenuated while across-group differences are accentuated.” (Kollock & Smith)1. AWF must differentiate itself from WF, and yet when contrasted with regular Facebook, the differences pale in comparison.

Much like WFB hijacked the Facebook, there is a double-hijacking that takes place in AWFB, which hijacks both the Facebook platform, and simultaneously co-opts the visual language of WF towards its own ends. AWFB both draws from and subverts memes from WF, with its own memes sometimes spilling into the greater memeosphere, but often remaining contained due to their inscrutability.

The reference pool of AWF contains obscure philosophers, scientists, thinkers, writers and historical figures, as well as the standard pop-culture pool of WFB, yet it treats them the same as other meme communities treat anime characters, funny animals, celebrities, video games, and other pop-culture memorabilia—with irreverence, vulgarity, absurdity and a general sense of playful disregard for context and appropriateness. Yet, there are also many make-shift conventions that govern the visio-linguistic usage of memes, which are ever-changing and context-specific, the rule often being to flaunt the rules—but always in an interesting way. “It is intriguing that digitally literate behaviors … require reversal of the grammatical and syntactical norms that typify literacy offline. The performance of digital fluency may thus require deviation from the literacy norm” (Papacharissi)2. In AWF, complicated and serious philosophical, scientific, and literary notions are expressed with emojis, texting abbreviations, low-brow sex and poop jokes, deliberate misspellings and various internet jargon. It’s a huge mess, but somehow it all works together.

Academic Weird Facebook is constantly expanding and evolving, and its own self-understanding is evolving alongside it. At once an emergent phenomena, a network of users, and an image-making vernacular, it is simultaneously isolated from the mainstream world, and also a bridge to meme-makers and consumers the world over. It is comprised of a myriad subdivisions, and I have outlined the big picture of the community. However, it is always experienced by its members at the ground level, so I have created a directory of meme pages and groups organized by subject so that the reader can easily find these communities and experience them as they are meant to be: by joining in.

Works Cited

-

Smith, Marc A., and Peter Kollock. Introduction. Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge, 2006. N. pag. Print. ↩ ↩2

-

Papacharissi, Zizi. “Without You, I’m Nothing: Performances of the Self on Twitter.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 6, 21 Nov. 2011. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Boyd, Dana M., “Taken out of context: American teen sociality in networked publics.” (Doctoral dissertation) University of California, Berkeley, School of Information. 2008 ↩